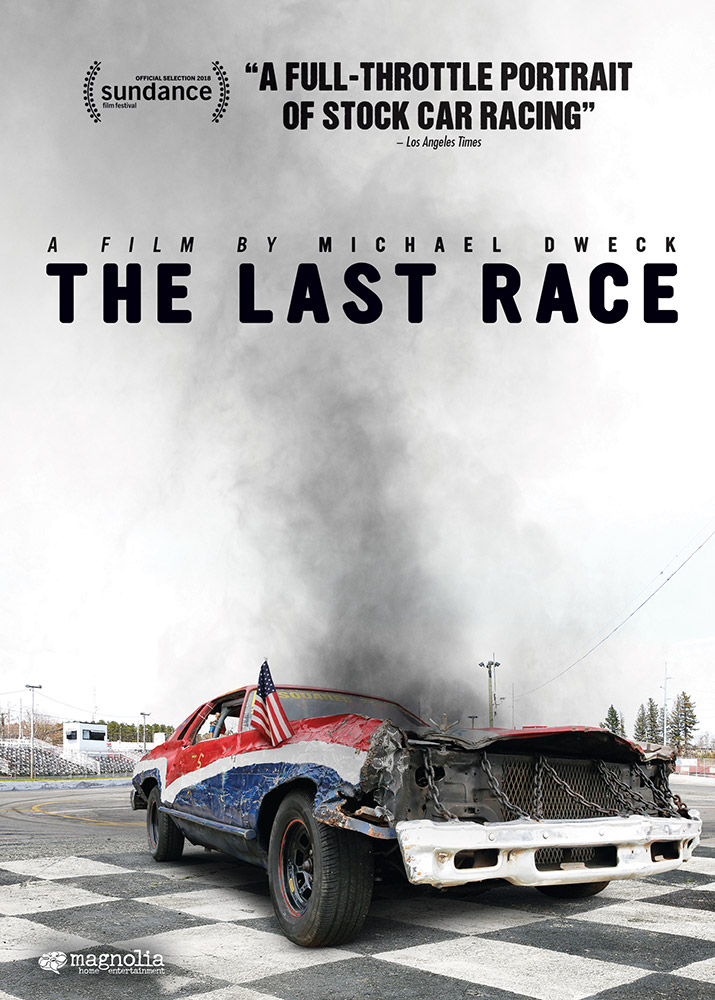

THE LAST RACE is an intimate portrait of a small-town stock car racetrack and the tribe of passionate blue-collar drivers that call it home, struggling to hold on to an American racing tradition as real estate development threatens its survival.

Award winning filmmaker Michael Dweck’s stirring imagery takes you inside the world of grassroots racing and eye to eye with the cars’ snarling grills and white roll bars that protrude like bones out of scarred metal. Yet a patient camera lets us know the drivers as everyday people and learn that the racetrack is tied to a deep sense of identity. The track is on the only piece of undeveloped land in the area—it's worth millions—and the only thing keeping the bulldozers at bay is track owners Barbara and Jim Cromarty’s love of the track and its community.

Directed by: Michael Dweck

Produced by: Michael Dweck & Gregory Kershaw

DIRECTOR'S STATEMENT

by Michael Dweck

I was three when my parents moved from Brooklyn to Bellmore in 1960, and some of my earliest memories are of watching the Bombers race at Freeport Stadium. The images of Wink Herold or Jerry "Red" Klaus scraping off the walls in turns two and four left their own scratches and paint on my childhood, as did the snarling sounds of cars I could hear from my bedroom window.

I began photographing at the Riverhead Raceway in 2007 as a way to reconnect with this simpler past – both mine and Long Island’s: the long Tuesday and Saturday nights at Freeport with my dad and brothers; the smell of burnt rubber and clutches; the heat radiating off the cars as they drove through concession areas blocked off by sawhorses on their way back to the pits; the sight – sometimes seen from a hole in the fence, when I'd go without my father – of railroad ties rammed loose and lodged like spears in wheel wells, protruding like lances as cars circled the tar track, sparks flying.

I was at Freeport on the last day of racing, Sept 24, 1983 (two days before my 26th birthday) and watched Peter "Buzzie" Eriksen become the last track champion. I watched the cars exit for the last time, driving on flat tires, dragging bumpers, or being towed – oil leaking and engines smoking. Sadly, it seemed the perfect metaphor for Long Island – even more so when I watched construction crews tear the track down to make way for a giant strip mall that opened, and closed soon after. Another heap for the junkyard, I suppose.

Riverhead Raceway is the last track on the Island. It’s only a matter of time before the bulldozers move in and Riverhead goes the way of other tracks before it, replaced by a shopping mall, or some other piece of disposable architecture. That’s what people want, and that’s okay. But when it goes, something will be lost.

THE LAST RACE is a celebration of a tribe of working class heroes and the track that has become the last bastion for their way of life. It’s an attempt to reclaim and capture the memories of my childhood so that the mysterious beauty that I once witnessed might still be known after Riverhead is gone. Moreover, this film is my creative effort to provide its viewers with a singular aesthetic experience-- to become active participants--and witnesses-- to the spirit of Riverhead, and explore questions of blue collar American identity that have taken on a profound relevance in the current political era.

PRODUCTION NOTES

From Cinematographer & Producer Gregory Kershaw

In the late fall of 2012, I was approached by Michael Dweck with the idea of making a film about stock car racing. Michael had been shooting still photography at the Riverhead Raceway on Long Island, not far from a shuttered track that he frequented as a child. Over the previous five years, Michael had spent the summer race season capturing the sculptural forms of the cars through large format photography and sculpture.Through his process as a fine artist and his summer residences at the track, he discovered images and a narrative that was beyond what still photography alone could capture. He came to me with the challenge of filming the unfolding story at the track in a way that would push the boundaries of conventional documentary storytelling, express the intensity of the racing experience, show the strange beauty of life at the track, and document the culture of blue-collar American racing in previously unseen ways. Through this challenge, we embarked on the journey of creating THE LAST RACE.

Through the fall and winter leading up to the summer race season, we began viewing a wide variety of films that would eventually serve as our inspiration and guide. Errol Morris’s early work such as GATES OF HEAVEN and VERNON, FLORIDA provided inspiration for capturing candid interviews with idiosyncratic characters and the distinct personality of a region. Louis Malle and René Vautier’s film, A HUMAN CONDITION, was screened for the way it captured a location that was simultaneously intimate and alienating. KOYAANISQATSI was a model for capturing movement and the symphonic merging of music and images. Classic racing films like GRAND PRIX, LE MANS, DAYS OF THUNDER, as well as contemporary NASCAR broadcasts were also viewed as a context for how auto racing has been mythologized in popular culture and provided insight into how that mythology was reflected in the culture of the racetrack.

In the months leading up to production, the urgency of telling the story around the track became more apparent. Long Island was the birthplace of stock car racing, and since its inception during the prohibition era, there had been over 40 different auto racing tracks covering the island. Every one of those tracks except the Riverhead Raceway had closed, and an explosion of development around the track seemed to signal that Riverhead was headed in the same direction. Forests surrounding the track were cleared overnight, and backhoes were breaking ground for big box stores. As we started talking to real estate developers in the area, we realized how much pressure was on the owners to sell. The value of the land far exceeded the earning potential of the race track, and its octogenarian owners, Barbara and Jim Cromarty, were facing health problems that made overseeing the operations of the track increasingly difficult. Although Barbara and Jim assured us that they planned to keep the track open, we continually heard rumors from developers about the increasingly outrageous sums that were enticing Barbara and Jim into a well-deserved retirement.

At the start of the summer race season, we realized that this could be our last chance to film racing on Long Island before the bulldozers wiped it off the map forever. Over the course of a long summer race season, we spent every weekend filming, and through the process, we became participants in the track’s culture. We were assigned a parking space in the pits where we set up our gear and managed our media. Our work soon became folded into the rhythms and rituals of the track. Being accepted into the family of the track came with all the complexity of being brought into any family relationship. Entering into their lives meant we got access to some of the racers’ highest highs but also meant we were fair game as recipients for their angry explosions when they lost a race, or when we caught them on a bad day.

Our continual presence at the track eventually enabled us to get beyond the performative personas that many of the drivers put on at the start of our filming process. Furthermore, for our non-interview footage, we attempted to film in wide frames, or with telephoto lenses that allowed us to maintain distance between us and our subjects. This, combined with a continually rolling camera inured our subjects to the filmmaking process. Likewise, the constant presence of our cameras in the cars during the races enabled us to capture some of the most emotionally raw footage of the film, such as the explosive anger of a fight brewing after a race, the unabashed thrill of a driver winning the championship, and the intimate rituals of preparation before the start of a race. During the summer weekdays when the racetrack was closed, we followed the drivers through their daily lives. The mundane drudgery of their work was often a sharp contrast to the chaos and excitement we filmed at the racetrack. However, as we filmed with the drivers off the track, we came to discover how the unique character of their lives on Long Island reflected their passion for racing.

The editing of the film was completed in Copenhagen, with Charlotte Munch Bengtsen. She was chosen to edit the film because of her background in unconventionally structured narratives, such as her work with Joshua Oppenheimer on THE ACT OF KILLING, but also because we were looking for someone who could bring an outsider's perspective to the subject matter. For her, entering into the uniquely American race culture of the Riverhead Raceway was both exotic and mysterious. Her perspective brought a new analysis of the material that unearthed new images and ideas that may have been taken for granted through our cultural familiarity.

The process of structuring the story merged techniques of photography editing with film editing. Screengrabs of every shot recorded during production were printed as still images and laid out for viewing. These images could then be pulled and ordered to create a visual narrative that supported the underlying story. This process led to the evolution of a narrative based on unexpected visual connections and contrasts. Unlike many conventional documentaries, the images are not mearly used a visual facade to cover a structure built on information and narrative conveyed through audio; rather, images occupy a deliberate position and work as building blocks of the story itself.

From the beginning of the filming process, we knew we wanted to capture the intensity of the car racing in a way that people had not seen or experienced before. To do this, we employed an array of small lightweight and inexpensive cameras that allowed us to frame shots in extremely vulnerable positions and explore new perspectives to capture the race. We experimented with a variety of mounting fixtures, including asking the drivers to weld mounts onto their cars. Eventually, we found that commercially available lightweight grip gear gave us the most options for camera placement and could provide robust, sturdy mounting points even in our extreme, high-impact filming conditions. Remarkably, not one camera was lost or even damaged throughout the entire filming process. For every race, cameras were placed around the track and on a variety of angles on the cars. One car could have as many as five different cameras capturing different perspectives in a single race. Through reviewing nearly a hundred hours of footage captured during the races we discovered unexpected moments of beauty and sometimes disaster.

The process of recording audio was equally expansive and experimental. During the production process, we built an audio library of the different sounds on the track. Certain sounds, such as the voice of the track announcer, were captured from numerous different recording possitions to reflect the many perspectives that the audio could be perceived from locations in and around the track. Racing sounds and a variety of different car sounds were also recorded from various perspectives to provide the sound designer with a broad palette of sounds to pull from for the racing sequences. The intention was for every car and every race sequence in the film to have a unique personality expressed through the audio.

The audio we collected during production was used in the sound edit to achieve an impressionistic rendering of the subjective feeling of the race track, rather than a literal one. This allowed us to take the chains off of structure and format to create a blur of music and crowds, and transition the sound design from scene to scene in a dreamlike way, with sonic elements slipping and sliding in layers. We used perspective shifts, audio pre-laps, extended transitions, abstract sound design, and both diegetic and non-diegetic sound, and non-diegetic music, often all in the same sequences, throughout the film.

DIRECTOR

Michael Dweck

Michael Dweck is an American contemporary photographer and visual artist. Best recognized for his evocative narrative photography, Dweck artistically investigates the on-going struggles between identity and adaptation found within endangered societal enclaves. Dweck's works have been featured in solo and group exhibitions at museums and galleries worldwide including the Museé du Louvre in Paris and the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles, and are part of prestigious international art collections, including the archive of the Department of Film at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, where two of his long-form television pieces reside.

In his first feature-length film, The Last Race (2018), Dweck extends his exploratory repertoire by combining observational documentary, stylized imagery, and a symphonic merging of motion and sound. Experimenting with both form and subject matter, Dweck highlights the mysterious beauty and exuberant passion shared by the last custodians of a disappearing tradition. Aside from creating an artistic appraisal of class and American identity, Dweck’s film allegorizes the broader, global epidemic wherein handmade objects and ritualistic traditions face extinction at the hands of mass conglomerate takeover.

Dweck’s other notable series of works include: The End: Montauk, N.Y., 2004, a paradisiacal photographic portrait of the famed fishing community and the beautiful denizens who comprise its surfing subculture; Mermaids, 2009, an impressionistic underwater dreamscape populated by storied “river children” in rural Florida; and Habana Libre, 2010, a prophetic narrative that contrasts the privileged lifestyles of Cuba’s creative class with the crumbling backdrop of a “classless” society. With this latter body of work, exhibited at the Fotoceca Museum in Cuba, Dweck became the first living American artist to have a solo museum exhibition in the country. Dweck’s latest project, Blunderbust, explores the multifarious angles of a small-stakes stock car racetrack through an ambitious mélange of sculpture, installation, abstract painting, photography, video art, and film.

Dweck holds a degree in Fine Art from the Pratt Institute in New York. During his earlier career as a highly regarded creative director, Dweck received over forty international awards, including the coveted Gold Lion at the Cannes International Advertising Festival. Michael Dweck currently lives in New York City.

GREGORY KERSHAW

Gregory Kershaw has worked on narrative and documentary film productions as a producer, cinematographer, and director. Most recently, he was a senior producer at Fusion television where he made environmental documentaries. His work explored the impact of climate change on indigenous populations throughout Latin America in a series of United Nations Foundation funded videos, as well as long form documentaries on the global species extinction crisis featuring environmental luminaries such as Jane Goodall and Sylvia Earle. Gregory is a graduate of Columbia University’s MFA film program.

EDITOR

Charlotte Munch Bengtsen

Coming from a background as a dancer and photographer Charlotte edited her first notable documentary AMERICAN LOSERS by Ada B. Søby in 2006. Charlotte soon realized she could bring all her tools together in this craft and decided to pursue solely the editing path. In 2009 she graduated from the National Film and Television School in England. Since then she has edited a number of award winning documentaries, including THE ACT OF KILLING (dir. Joshua Oppenheimer, 2012), TANKOGRAD (dir. Boris B. Bertram, 2010), COMPLAINTS CHOIR (dir. Ada B. Søby, 2009), THE BASTARD SINGS THE SWEETEST SONG (dir. Christy Garland, 2012), PETEY & GINGER (dir. Ada B. Søby, 2012), A WHITE MAN STORY & QUEEN OF THE GODS (dir. Linus Mørck, 2014 & 2015), next to numerous tv-series produced by DR (Danish National TV). Currently Charlotte is working on the documentary WAR PHOTOGRAPHER (dir. Boris B. Bertram, 2016/17) and THE LAST RACE (dir. Michael Dweck, 2016/17).

SOUND DESIGNER

Peter Albrechtsen

Peter Albrechtsen is a sound designer and music supervisor based in Copenhagen, Denmark. He graduated from The Danish Film School in 2001 and has since then worked on more than a 100 productions and done both feature films and documentaries, both domestically and internationally.

Among Peter Albrechtsen’s recent credits are the multi award-winning The Queen of Versailles and festival favorites Putin's Kiss, Canned Dreams and The Bastard Sings the Sweetest Song. At CPH:DOX 2012, Peter was awarded the 'Sonic Dox Award' for the sound design of White Black Boy. At the same time, Peter has been working on a long list of fiction films, one of the latest being last year’s Sundance winner Teddy Bear and previous work include sound effects editing on both The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2009) and Lars von Trier's Antichrist (2009). Peter is a member of the US association of sound designers, MPSE.

Along with his work as sound designer and sound re-recording mixer, Peter Albrechtsen has worked as a music supervisor and among Peter’s latest work in this regard are the festival favorites I’m Fiction and Dance For Me and the feature film You & Me Forever, which earned him a Danish Academy Award Nomination for Best Sound Design. He has collaborated closely with globally acclaimed musicians such as Antony and the Johnsons, Jóhann Jóhannsson and Efterklang.

Peter has also written about music and movies for different Danish and international magazines and has been moderating seminars and teaching at The Danish Film School and the international Animation Workshop in Viborg.

MUSIC COMPOSER

Roger Goula

Roger Goula is a London based composer and multi-instrumentalist. Coming from a contemporary classical background, Goula’s work has developed into an experimental blend of classical chamber and orchestral music with electronics.

Inspired by renaissance and baroque music, as well as by minimalism, and looking at the language of electronic music, his compositions perform complexity through repetition of minimal elements and emotional transporting textures. Most recently his been commissioned by the acclaimed string quartet Experimental Funktion a 30min piece to be performed along side Steve Reich ‘Different Trains’ and premiered at the CCCB of Barcelona in December 2013 as a closure concert of the BCNmp7 Music Festival.

Composing also across platforms including film and tv, dance, theatre and art installation, Roger has worked for a number of award winning films such as Next Goal Wins, Shock Head Soul, Brand New-U and the ITV series The Frankenstein Chronicles. At the moment he is scoring the latest film by Charlie Bellville featuring Tom Hardy as lead actor. This year his solo debut album Overview Effect will released by the new label Cognitive Shift in collaboration with One Little Indian, and includes collaborations with notable performers such as Peter Gregson, Thomas Gould, Lucy Railton, Stephen Upshaw and Claudio Girard.

Roger Goula studied classical guitar in Barcelona and graduated in music composition from the Goldsmiths College and in film music from National Film and Television School. He also studied composition with Michael Finnissy.